Haiku explained by Gabriel Rosenstock and discussion about poetry with poets

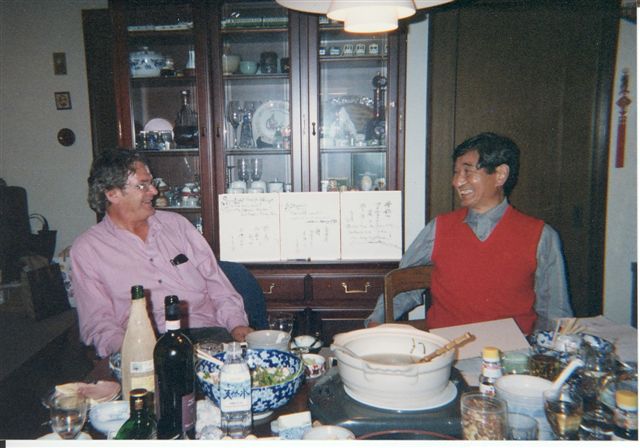

Gabriel Rosenstock and Prof. Shinku Fukuda

The hokku became autonomous in due course, i.e. it detached itself from the renku, and is today's haiku.

A haiku is not a poem. If you want to write poetry in a Japanese style and write 5 lines instead of three, there are other forms available to you such as waka and tanka.

Werner Wolf, The Lyric: Problems of Definition and a Proposal for Reconceptualisation, in Theory into Poetry. New Approaches to the Lyric, Eva Müller-Zettelman & Margarete Rubik (eds.), Editions Rodopi, Amsterdam – New York, 2005, 375p, pp. 21-56

One of the principal reasons for the difficulties arising in defining the lyric resides in the history of its designation: (…) ‘lyric’ has become an umbrella term for most versified literature (except for the epic and verse drama) and has thus become a synonym of ‘poetry’.

(p.22-23)

(…)

So, must we conclude that the general consequence (…) is (…) that ‘the lyric cannot generally be defined’ (…)? The answer must indeed be ‘yes’.

(p.31)

(…)

The terminological development and the ensuing heterogeneity of the texts that have been called ‘poems’ create enormous problems for the attempts that have been made at establishing systematic criteria for the lyric. (…) There are only two basic features that are unproblematic, since they constitute the common literary ground in which the lyric is embedded and where it is supposed to coocupy a particular domain (notably as opposed to drama and narrative fiction), namely that a poem is a literary text and that (p. 23) it is fictional. (p.24)

(…)

(T)he functions of the lyric as well as the generic expectations raised in the recipients should form part of the generic description and that something ought to be said about the markers or the framing of the frame ‘lyric’. (…) (A)n approach to the lyric that is

a) above all cognitive and prototypical in that the lyric is here conceived of as a cognitive frame based on plurifactorial prototypes; apart from that it is also

b) communicative in that it does not merely focus on textual traits but also on the ‘sender’ and the recipient, for instance on his or her ability to identify poems as such, and

c) functional in that it also embraces typical functions fulfilled by lyric discourses as well as typical expectations raised by it.

(p.35)

(…)

As for the functional side of the matter, the lyric can be described as a genre that fulfills (…) functions (…) (that) can be summarized (…), and their inclusion in a list of prototypical components of the lyric (…):

- potential orality and performativity without dramatic role-playing: in sptie of the existence of poems that presuppose a written form, the lyric – not least owing to the importance of the acoustic reality of its signifiers – has retained more affinity to orality and performativity thn narrative fiction; as for a distinction of the lyric from drama as a rivaling performative genre, the tendency of drama towards role-playing is so self-evident that the lyric’s significantly lesser tendency in this direction, together with its at least relatively prominent orality, yields a sufficient difference for maintaining this feature as a prototypical trait of the lyric 43;

- shortness: with a view to the majority of poems, this is an obvious prototypical trait;

- general deviation from everyday language and discursive conventions resulting in a maximal semanticization of all textual elements: again this trait appears to be self-explanatory with reference to the majority of texts;

- versification (acoustic or visual) and general foregrounding of the acoustic potential of language including rhyme (‘musicality’) as interrelated special cases of deviation; considering the majority of poems it would hardly be possible to deny that this trait is in fact also widely typical of the lyric;

- salient self-referential and self-reflexivity as another special case of deviation: while self-reflexivity may seem obvious enough as a prototypical trait of most poems, self-reflexivity is perhaps not found in the majority of poems; however, the lyric appears to be the genre in which this feature has played a greater role throughout its history (and not merely in modernism or postmodernism) than either in drama or in narrative fiction, so that meta-poetic self-reflexivity can be said to possess at least a relative characteristic salience;

- existence of one seemingly inmediated consciousness or agency as the centre of the lyric utterance or experience (creating the effect of ‘monologicity’ of lyric discourse): again, although in many cases this feature will not be applicable, it is arguably relevant for the majority of poems and thus fulfills the condition of a prototypical trait 44;

- (emotional) perspectivity and subject- rather than object-centredness (emphasis on the individual perception of the lyric agency rather than on perceived objects): this trait appears valid for the same reason as trait no.6;

- relative unimportance or even lack of external and (suspenseful) narrative development: again, in spite of examples to the contrary, this feature can be justified as prototypical of the lyric, in particular if it is opposed to both narrative fiction and drama, which both typically – and much more regularly than poetry – represent stories, albeit in deifferent forms of transmission 45;

- ‘absoluteness’ of lyric utterances (dereferentialization): again, this trait appears to be valid, since its inclusion in the list only implies – as is the case with the other eight traits – that it is applicable to a majority of relevant texts.

(p.38-39)

Philip is of course right (in general &) particularly with regard to Norb Blei's

Athens 11.7.2013

Dear Philip,

that is a tremendous contribution and does certainly take us from writing in Haiku form to what constitutes poetry in its varied forms.

Let me allow to mark one difference. When Gabriel stresses the 5-7-5 form, I take that to mean a constraint has been set so that anyone wishing to make the claim to write a poem in the form of a Haiku, he or she will have to confirm to this rule. Gabriel says it in so many words: to bring about the visionary power of saying something in only so many words, flabbiness has to be avoided by taking even one extra word on board - with the exception of Basho.

Creativity can be brought about by setting a constraint. For example, you bring together all kinds of artists and you tell them they can express anything they want but it must be done on stone. That then is the constraint. The art of setting a good constraint explains as well how creativity is brought about - precisely by not everything being allowed.

Thus the setting of a constraint differs from trying to define what is poetry.

It is also another matter when people in general, and not only academics, agree on what is a good poem. What speaks to them, lets them feel something! It may rest on a cultural consensus as to what poetry is all about in our daily lives, and not only when there is a special reading with poetry being performed for an audience expecting to hear now poetry, and not just any poetry but from an already recognized poet. The latter entails already some pre judgement fortified by formal recognitions. It starts with publishers and literature houses but does not end when critics have stated their opinions.

What I miss in your list of possible attributes to be considered when calling something a poem is for what purpose was set free the energy. What was meant to be addressed? I gave the example of Ritsos who would write a poem after someone had been killed for political reasons and he wrote the poem to keep this man in memory, or in other words, alive. For there is something which cannot be killed. Upholding freedom even while in jail as he was so many times gives also another example of what it means to devote poetry to keep alive not only language, but a language which dignifies the human being. You write to live, to be free, even when behind bars. That is resistance against all negative determinants.

So I would not think that when discussing poetry you enter necessarily a dangerous territory. That would only be the case when it is claimed that that there is a set definition of poetry, and nothing else would therefore exist. Adorno considers all terms we use in the social and aesthetical sense as being at best open definitions. As we learn we refine the original version and thereby deepen our understanding as to the meaning of poetry to ourselves.

I went the other day to a poetry reading. I was curious if I could tell when listening to what the poets were reading out aloud. I got the impression most of the time they were trained at creative writing schools or in poetry workshops to think about poetry in terms of definitions in need to be fulfilled. That was no longer poetry but a kind of mental exercise, and done so with a clear imitation of what they thought to have influence upon an imaginary audience. Thus one poet imitated the voice of the priest in an Orthodox church and likewise his poems became like the prayers sung rather than spoken as if plain words would not do. One other poetess spoke about wounds and poetry helping to survive when the country like Greece is in crisis, but when listening to her poems I could not sense the wound nor see the crisis. The poet turned priest he repeated in every poem death and had at the same time seagulls flying over his head as if standing on a ferry boat when traveling to one of the Greek islands.

Thus I would come back also to Foucault who reminded that even when someone stumbles over words, and hardly brings forth a coherent sentence, he may be much closer to the truth than some smoothly said verse filled with supposed meanings which have been collecting like dew drops on a cold water pipe or like bats in a cave only to be frightened if you light up a torch. But I do not mean a poem needs to be authentic in relating only to some personal experience. Rather drawing out some unexpected truth not seen before can be just as revealing to the poet as to the audience.

Thanks, and like Yiorgos before, it is most helpful when we depart from set definitions and take the meaning of what is a poem or not to be something to be questioned, for every poem is an attempt at an answer to what we seek to know.

hatto fischer

On Thu, Jul 11, 2013 Najet Adouani, poetess from Tunesia but right now living and writing in Berlin said something very important:

and then Yiorgos Chouliaras wrote:

Dear Hatto & friends,

On Thu, 11 Jul 2013 12:39:04 +0200, Philip Meersman wrote:

Concerning Haiku: It is indeed difficult to transform the ideograms (which in the original form were all on 1 line also) into this 5-7-5 western translation.

In Universe of the Mind, Lotman defines it as “the semiotic space necessary for the existence and functioning of languages, not the sum total of different languages” (123) The semiosphere asks us to consider, not a particular language with its own well-developed grammar and self-description, but the way each language interact with all the others around it: “In this respect a language is a function, a clister of semiotic spaces and their boundaries, which, however clearlu defined these are in the language’s grammatical self-description, in the reality of semiosis are eroded and full of transitional forms” (123-24).

The interactions among languages can be seen as acts of translation, which is for Lotman a fundamental process of information generation, “a primary mechanism of consciousness. To express something in another languages is a way of understating it” (Universe of the Mind, 127). But translation is also a way of changing a message: as any translator knows, and as Lotman emphasiszes, most translations generate new information. The original message is altered and augmented in being transmitted from one code to another. Thus translation is never a simple re-creation of an idea in a new code; it is never a transitive equation if identity. This irreversibility if translation helps account for the “erosion” and (p.324) “transitional forms” at a language’s boundaries. It also helps explain why the semiosphere is more than the sum of its parts, since the mutual translation among languages generates new information, not to mention entirely new languages. Indeed, one function of the semiosphere concept for Lotman is to explain how different languages can exist in continuous conflict and dialogue within a culture, along many different axes, forming an organic whole that never stops evolving. “As against the atomistic static approach we may regard the semiosphere as a working mechanism whose separate elements are in complex dynamic relationships. This mechanism on a vast scale functions to circulate information, preserve it and to produce new messages” (Lotman and Uspenskij, “Authors’ Introduction,” Semiotics of Russian Culture, xii).(p.325)

Good poem: interpretation, giving meaning, and tastes change with the different tastes, periods, history, cultures,... so what is considered a 'good poem' now, will not perhaps be seen as a good poem in the future, same goes for the past. Look at symbolism, Mallarmé, surrealism, impressionism in painting, futurism, Dada, Zaum, Minimalism, sound poetry, slam poetry, visual poetry, the new interest in all these avant-garde art expressions of the beginning of the 20th century that were mostly condemned by critics, academics,... in their own time and/or in there own country (or language area)...

As Duchamp already stated (one version on his theory of The Creative Act can be found here: http://www.cathystone.com/Duchamp_Creative%20Act.pdf) a piece of art is only complete or 'made' once the audience has also made its interpretation of it. The same applies also for a poem.

Some poems, and art in general, are seen just after their exhibition as repulsive, bad, not good, pornography, not art,..., or even as an act of iconoclasm (for more about that see the work of Gamboni: Destruction of Art (http://www.amazon.com/The-Destruction-Art-Iconoclasm-Revolution/dp/1861893167) (a critique of this work you can find here for those who do not have that already in their library: http://www.arlisna.org/artdoc/vol17/iss1/14.pdf))

I'm thinking that in this post-post world we live in we should not go with definitions but more with fields, semiospheres, loose bordered areas in which there are centres within which very clear cut examples of 'poetry' or 'art' or ... are sitting there and the peripheric areas where there is a permeable field of transmediality or intermediality.

For a better understanding see Irena O. Rajewsky, Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality, in intermédialités no 6 automne 2005, pp. 43-64

Trying to reduce to a common denominator the host of current conceptions of intermediality and the vast range of subject-matter they cover, we are forced to appeal to a very broadly conceived concept which would be limited neither to specifi c phenomena or media, nor to specific research objectives. In this sense, intermediality may serve foremost as a generic term for all those phenomena that (as indicated by the prefi x inter ) in some way take place between media. “Intermedial” therefore designates those configurations which have to do with a crossing of borders between media, and which thereby can be differentiated from intra medial phenomena as well as from trans medial phenomena (i.e., the appearance of a certain motif, aesthetic, or discourse across a variety of different media).6 (voetnoot 6: An example for this is the aesthetic of futurism, which was realized in different media (text, painting, sculpture, etc.) with the formal means specific to each medium. The concrete realization of this aesthetic is in each case necessarily media-specific, but per se it is nevertheless not bound to a specifi c medium. Rather, it is transmedially available and realizable, i.e., available and realizable across media borders. In a similar way, one can speak of a transmedial narratology, referring to those narratological approaches that may be applied to different media, rather than to a single medium only.) (p.46)

And yes, poetry is not alone about the most individual expression of the most individual emotion (the '90s movement in the Low Countries around the 1890s defined poetry like that) or not solely Wordsworthian landscape descriptions nor alone political critical manifestoes...

I can go on for longer, but since I'm not a keen fan of very long and extensive e-mails myself, I must try to not indulge myself in going on and on about this.

But surely, worthwhile to consider this - our discussion - for a published discussion, conference, publication on your website and/or in other forms...

All the best,

Philip

Athens 11.7.2013

Dear Philip,

you did not really respond to my wish to distinguish between the setting of constraints and definitions. Yiorgos did point out this interesting thing of what can happen when writing poetry, namely that we set new constraints. There is naturally an ethical vision behind this saying of 'not everything is allowed'. It appeared by Dostojevsky who asked is everything allowed once God is dead? In part poetry and literature is to keep that moral vision of mankind alive, and not necessarily depend upon a God or some other kind of formal authority.

But your extended answer is not too long. Rather you know dip into what are various ways of making use of poetry if it is like a ritual or else easy to be memorized as Satchi just pointed out right now in the latest contribution.

Most interesting I find in your second reflection the use of the word 'space'. That is a most difficult concept, and can have as well political connotations. For what space we give, what space we take away? Foucault defined then the art of doing something as the creation of space without occupying it oneself. To give meaning in life is, therefore, not destroying it to make for the new but we do know at times this slogan became a forerider of Capitalism per say, namely through destruction people become creative. They need to survive and struggle with what is left after a war, but then again the crucial question would be if poetry can prevent a war?

Staying with space, I received a wonderful letter from Merlie. I hope, Merlie, that you do not mind me quoting you at length. For Merlie gives an account of how she has been invited along with other poets to help create a new space, the Asian space. It is like a political realm in which similar to the European Union a set of values and assumptions are shared, and therefore such a space can set free the imagination to live not confined to smaller spaces like a village or nation but to a larger realm of political influence. Naturally we know about this tendency from the European Union which has just welcomed Croatia to become member Nr. 28 with still more waiting to join. That reminds of a saying by Hegel, namely bourgoisie society knows only to exist by expansion.

Here then the letter of Merlie M. Alunan in the Philippines which I would like to bring at this point into the discussion for many reasons:

„I was in the last quarter of June in Bangkok, Thailand to accept an honor as an ASEAN (sic) poet from the Thai Government. On the whole these had been satisfying events that gave one hope for poetry at the same time that it makes one think what a lot needs to be done and how utterly small the poets' voices are against the roaring giants we are fighting. Nevertheless one must be grateful for little blessings.

The Bangkok interlude is a Thai initiative with very strong political overtones--its stated aim was to forge unity among the ASEAN nations through the agency of literature, particularly poetry. They set up the Sunthorn Phu Award for Poetry for ASEAN poet laureates. The poet laureates were to be named by their respective countries,.And that is how I got to be chosen to represent my country in this event.

ASEAN unity is a will o' the wisp, as you can imagine, with its diversity of cultures, histories, widely divergent political systems, stages of postcolonial recovery, or suffering war, border clashes, internal unrest, and above all, diversity of languages. The operative catch phrase of the event was to open up the ASEAN skies through poetry. So much hope vested on so frail a vessel. The opening up of the poetic skies of ASEAN, it looks to me, depends on what the first ten poet laureates will do. Since we are not organized as a group, our linkages would have to be forced on the basis of personal commitment. We have informally drawn up our plans and I should be working on this soon. At the moment I am catching up with interrupted work, but already I feel the urgency to make the linkages work.

Sunthorn Phu was a poet of the royal court of Thailand in the 17th century. He lived through four kings, surviving by turns in honor and infamy, poverty and wealth, beggary and power, as he runs through favor and disfavor with the ruling monarch. But he always acted as he saw fit, no matter what he had to pay, to act as a free man. To this day he is honored as the Poet Laureate of Thailand, his works are part of any Thai child's upbringing and continue to nourish contemporary art in Thailand.

Your concerns about Greece and the European Union, freedom of speech and communication, the life of the imagination, intellectual freedom are the same concerns we face in the ASEAN Region, perhaps in a worse way, because of repressive regimes, religion and ideology, and adherence to durable traditions. This is the world I inhabit, a world you may find puzzling maybe, nevertheless once past the surface, it is the same world in which the poet is struggling for space to create, in which his work puts him in all kinds of dangers. Still he goes on because of certain convictions, proven or not, that as long as he exists, humanity has a chance.“

Her new task reminds of what the City of Toronto did when asking a poet to lead the way to imagine the city. By attributing to poets the imaginative power, it means also to discover other spaces (niches) to exist even with such a small voice like birds do in midst of Manhattan.

That then can lead over to the suggestion by Yiorgos and to which Philip has agreed to already, namely to start reflecting and then by 15th of August collect on the basis of this discussion an essay of each one of you on this theme as to whether poetry can set free the imagination so that it becomes possible to relate to others as human beings, and in the spirit of being free as human beings to express ourselves in the languages we know best to articulate?

I imagine that this question can easily be altered into what is the defining power of poetry if not poetry itself, but what happens to poetry once one gives in to other than poetic definitions and which want to make use of poetry for a certain purpose? Remember what Freud said about poetry: it can be used to establish a new rulership based on a myth. Virgil and the Roman Empire considered myth as the best tool to remind people what they would have to do at a certain time period e.g. when it is time to harvest. In today's world the connection to the seasons has disappeared as work in neutral offices and everyone behind the computer screen more a cyber bee than someone who would be able to look back at the end of the day and could count the number of lanes ploughed already, and what work lies ahead therefore the next day.

ciao

hatto

The answer by Philip:

‘ Serbo-Croat is, of course, a language that falls easily into verse and until recently was encouraged to do so on all occasions above the ordinary: when the great American foreign correspondent, Stephen Bonsal, first came to the Balkans in the eighteen-nineties he was enchanted to hear the Serbian Minister of Finance introducing his budget in the form of a long poem in blank verse. The logic is obvious. A free people who could make their lives as dignified as possible would naturally choose to speak in verse rather than in prose, as one would choose to wear silk rather than linen.’

( ‘Black Lamb & Grey Falcon’: Rebecca West, 1941.)

On Thu, Jul 11, 2013 at 4:46 PM, Rati Saxena wrote:

In Indian history most of the books related to other knowledge written in poetry form. Astrology, mathematics, science, medicine and grammar... every knowledge got language of poetry. Great Mathematician Bhaskaracharyas great work - Lilavati was a fine poetry, see a few lines from the book. The story goes as follows:

Whilst making love a necklace broke.

A row of pearls was mislaid.

One sixth fell to the floor.

One fifth upon the bed.

The young woman saved one third of them.

One tenth were caught by her lover.

If six pearls remained upon the string, how many pearls were there altogether?

Satchid Anandan quipped with his own question:

Oh, the mathematics of love making that makes one love mathematics! "Lilavathi", the book's title itself means the playful woman. Can I have the remaining pearls please?

To which Rati responded with an extension of the story:

She was Bhasker#s daughter, and also a great mathematician. However, there is a sad story behind it. Bhaskara knew also astronomy, so he could read the future of his daughter according to which if is she is not married at certain time or in a certain period, she would be a widow. So Bhaskara made a Yantra which could show the crucial time. He made this yantra in Water, and kept it in one room. He asked people not to open that room, but Lilavati was a playful girl. So she went into that room and started peeing in that Ynatra. Some how one pearl from he nose ring fell down, into the water of that yantra and from then on the time machine went wrong.

Not knowing this episode Bhaskar married his daughter at the time as showed by Yantra and soon after marriage she was a widow. Bhaskara was very sad. He started teaching math to his daughter and wrote a great book of mathematics and give it the name Lilavati after his daughter...

It is said, she had also written some books, but we lost lots of literature and books... Any way, love was the main theme of the thinkers of that time, as we all know.

After Rati told that story, Satchi quipped:

Oh, the mathematics of love making that makes one love mathematics! "Lilavathi", the book's title itself means the playful woman. Can I have the remaining pearls please?

and from James Ohara in Santa Fe responded as follows:

Rati,

While the translation into different languages continues of the Haiku poem by Norb Blei, the discussion turned again back to Haiku as form itself. It started with George correcting Gabriel.

Friday 12.7.2013

George Szirtes

To which Hemant Divate responded:

That was followed by another reference to the original form in Japan:

Out of the immense varieties of poetry such Japanese verses have special qualities to be called poetry of a special genre - I differ with you poet Divate

- Aju Mukhopadhyay

Dear Aju

Hemant

To which Aju Mukhopadhyay replied:

May be you have mixed it with the other things, but of course people may differ. Haiku is three liner- syllabic and usually it is on Nature- but there are other types in the same Japanese genres. Poet Tagore after visiting Japan introduced it in India and wrote in favour of such poems. Short verses have immense values. I have written essays on it and one last thing I say that such poems are being practised now throughout the globe and large number of ezines and websites carry them. But after all, we may be guided by our ideas and of course, differ.

Aju Mukhopadhyay

Gabriel Rosenstock let it be known in this discussion that:

Gabriel

Aju Mukhopadhyay asked then in turn:

Right but if some people don't like them what could be done!

Athens 12.7.2013

Dear Aju, Hemant and Gabriel,

anything coming close to being merely ritualized has inherent dangers. Hemant wishes to draw attention to what has given rise to globalization and whatever forms accompany it. Rightly so he criticizes the undercurrent as being Romantic.

Now we do not wish to be didactic but give more space to various considerations as to what poetry can do. And as I said already in my reply to Philip, Haiku reflects the art of setting a constraint under which something is brought about.

Aju, you emphasize the beauty of some short but meaningful expression. Here we can wonder how words put together make all of a sudden more sense than in any other context.

So if we wish to reflect further on this, let us continue the discussion already started under

http://www.poieinkaiprattein.org/poetry/haiku-poetry/haiku-explained-by-gabriel-rosenstock/

There has been made even the proposal that we do collect a series of articles on what makes poetry so relevant to our times. The deadline is set for 15th of August.

Naturally spontaneous responses is what seems best suited for poets: immediacy being created while the world clock ticks away. We do and want to live in the presence of others. So if Gabriel says Haiku is not only poetry but a way to live, then it would have to mean becoming free from the need to have 'Gebrauchsanweisungen' - recipes - on how to live. Rather you smell it and touch life even when as Dileep says about Ritsos he denied himself all senses in order to touch something before he could see it. This is entailed in the poem 'the Potter' by Ritsos

It can say that poetry is the freedom to live your own craziness, provided you do not harm anyone else by living it.

ciao

hatto

Temporarily back on the internet - Yiorgos reclaims the electronic space Friday late afternoon - just in time:

Sent from my iPad

« Photo Haiga | Interview with Gabriel Rosenstock »